The Hydrogen Briefing

AP

RenewablesNewsHydrogen. It seems everyone's talking about it these days. From transport, to energy storage and even manufacturing, it's being touted as the next big thing in clean energy and a panacea for our global reliance on fossil fuels

inspiratia has been delving into the weird and wonderful world of hydrogen through our podcast series, where we've discussed the technology with energy gurus like Jigar Shah and hydrogen pioneers like ITM's GrahamCooley and H2GOPower's Enass Abo-Hamed.

Our deep dives into hydrogen storage, hydrogen vehicles, fuel cell mobility and electron stewardship in Orkney are all well worth a listen to for those who want a comprehensive understanding of the issues around its commercial application.

But if you're not yet up to speed on how we can utilise the most abundant chemical substance in the universe for the energy transition, here's a digest.

What is hydrogen?

The element that makes up 75% of matter, hydrogen can be produced for commercial use in an electrolyser by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity. The process is called electrolysis.

Not a source of energy, but rather an energy carrier, hydrogen is attractive for industrial uses because it is light and has a relatively high energy content per unit of mass.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) demand for hydrogen has risen threefold since 1975. The market today is worth more than $100 billion (£77bn €91bn) a year and is growing at a compound rate of around 6% per annum.

However, most hydrogen produced through electrolysis uses electricity generated from fossil fuels and therefore has a carbon footprint. This is known has "grey" hydrogen.

"Green" hydrogen, on the other hand, uses electricity sourced from renewable generators, but only accounts for a tiny fraction of the current hydrogen market.

You may also hear about "blue" hydrogen, which combines the use of fossil fuels and carbon capture technology.

While blue hydrogen is seen as a stepping stone to a more sustainable future, much of the focus is now on scaling up cleaner green hydrogen production.

More on electrolysis

Conversion efficiency - or, more simply, how much calorific value you put in to the electrolyser versus how much you get out - is an important consideration, as is the type of technology you use.

The two types of electrolyser currently available, Alkaline and Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM), have conversion rates of around 65 – 75% (lower heating value).

Alkaline electrolysers, which have been around for over 100 years, are cheaper on a per kWh basis and have double the life span of PEM systems. But the newer PEM units have been rapidly gaining ground as they are more flexible and reactive.

High temperature prototypes are also in development and could bring with them conversion efficiency rates of around 90%.

How can hydrogen be used?

One of the reasons pundits are so excited about the technology is its versatility and the myriad applications it can have across different sectors.

Most obviously, green hydrogen could substitute grey hydrogen in energy intensive industrial processes which already use the substance as a feedstock, thereby reducing CO2 emissions.

In the steel industry, hydrogen is used in the heat treatment of steel billets and in the chemicals sector it's employed in the production of both methanol and ammonia - a staple of global fertiliser market.

The EU's Hydrogen Council also says it could help decarbonise cement production, aluminium recycling and the pulp and paper industry.

Its newer applications are equally compelling. In transport and mobility, the burgeoning possibilities of fuel cells - which use hydrogen as a component - are becoming increasingly attractive.

Hydrogen based clean fuels could be deployed across the transport sector - on roads, rail and in even in the air.

What's more, the use of hydrogen to power vehicles - unlike the types of batteries that currently power EVs - doesn't require the widespread rollout of charging infrastructure. It is also easily dispatchable.

Advocates argue that rather than being in competition with electric mobility systems, hydrogen could be applied in different use-cases to complement batteries in the energy transition. Hydrogen might, for example, lend itself better to long-range heavy duty transport like trucking compared to batteries.

Hydrogen fuel cell

Power

For some, though, hydrogen's real potential lies in what it can do in the power sector through the provision flexible generation and storage. In addition to providing dispatchable power generation in gas peaking plants, hydrogen can also act as a buffer to increase system resilience and help integrate intermittent sources of renewable power onto the grid.

Hydrogen may also be better placed to provide large scale, long duration energy storage. Unlike batteries, it can extract excess power in the summer months from wind and solar farms and discharge energy at times of low generation months later during winter, thus addressing one of the key challenges in the renewable sector.

Another interesting concept is power-to-gas storage, which would involve taking energy from a electricity network by way of electrolysis and storing it in the gas network.

The power-to-gas storage capability is especially relevant in the UK, where the gas network is three times the size of the electricity grid.

Advocates say the power-to-gas storage model combines the problem of an increasingly constrained electricity grid with the need to decarbonise a gas system - which is methane based - providing an economic and logistical solution.

So what's the problem? Balancing costs.

There are a couple of crucial barriers to commercial deployment. The biggest is cost.

Green hydrogen is expensive to produce. It can cost around eight times more than hydrogen produced using fossil fuels and is about ten times more expensive than natural gas.

Current prices for green hydrogen usually range from €3.50-5 per kilogram compared to around €1.50 per kilogram for grey.

Advocates say, however, that it will experience a steep decline in capex in the coming years. The IEA's analysis suggest costs could fall 30% by 2030.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance predicts steeper drops - to $1.40 per kilogram by 2030 and $0.80 per kilogram by 2050, and McKinsey's recent report predicts a fall to $1-1.50 per kilogram (in optimal locations) in the next five to ten years.

Different factors affect the price including the cost of electrolysis and, most importantly, the price of renewable power.

Andrew McDowell, vice-president of the EIB, has said when the average wholesale price of clean electricity falls to €0.02 ($0.022) or €0.03 per kWh (€20-30/MWh) green hydrogen will be cheaper than natural gas and this could be a turning point for the sector.

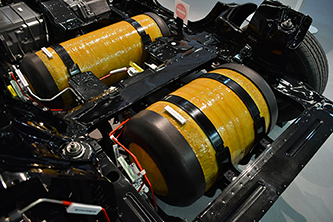

Hydrogen gas tank

The perils of storage

Because hydrogen is extremely low density - it's 3.2 times less dense than natural gas and lighter than helium - there are also safety and logistical considerations around storage.

Hydrogen can be stored as compressed gas in high pressure tanks, as a liquid or as a solid if it is mixed with another chemical compound.

Compression is technically challenging - and expensive - and the gas requires complex pressurised tanks when transported. If you chose cryogenic methods to cool hydrogen to form liquid, it occupies three times the volume of gasoline for the same amount of energy.

You can also combine hydrogen with certain metals which act as sponges for the substance, forming a solid, but this makes it extremely heavy which also brings its own cost considerations.

Needless to say, as hydrogen is deployed at scale on a commercial basis, developers and investors hope to bring their collective energy to bear on these constraints.