Floating offshore wind keeps gaining ground

EU

RenewablesMarket UpdateFloating offshore wind (FOW) garnered a lot of attention in 2020 as an increasing number of companies and governments kept noticing the emerging technology's full potential. Several countries have announced their FOW tenders for 2021, therefore we can expect continued activity

So what exactly are FOW turbines' advantages over traditional bottom-fixed offshore wind turbines? It is simply the case that winds are stronger and more consistent further out to the sea, and close to 80% of the world's offshore wind resource potential is in waters deeper than 60 metres.

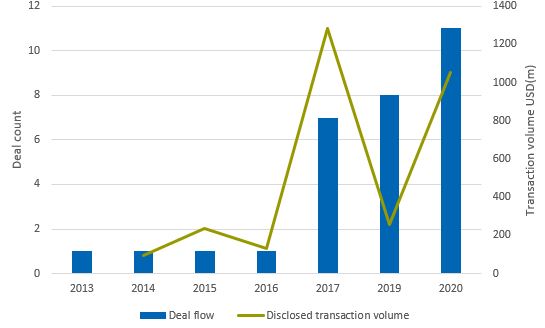

According to inspiratia's proprietary database dataLive, 2020 has seen significant FOW activity.

2020 saw a total of 11 FOW projects – the highest number of FOW deals tracked by dataLive in a year. Increasing activity has been observed for the past few years, with the biggest jump in the number of deals being from 2016 with only one deal to 2017, a year which saw seven deals.

Interestingly, 2017 had a higher value of disclosed transaction volume of US$1.3 billion (£961m €1.1bn), compared to 2020 with US$1.1 billion (£778m €858m). This was largely due to a series of floating wind tenders that took place in France.

France's Ministry of Ecology, Sustainable Development and Energy selected four offshore zones that bidders in the tender would compete for: Zone 1 – Groix, Brittany, Zone 2 – Faraman, Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur, Zone 3 – Leucate, Languedoc-Roussillon, and Zone 4 – Gruissan, Languedoc-Roussillon.

The floating wind programme was supported by France's €150 million future investment programme, split between the successful projects, and 20-year feed-in tariffs of between €200 (£160 US$228) and €250 (£200 US$285) per MWh.

Floating offshore wind activity, 2020

|

Project |

Country |

Transaction Stage |

Financing purpose |

Transaction Value (USD m) |

|

Norway |

In procurement |

Primary financing |

- | |

|

Norway |

In procurement |

Primary financing |

27.5865 |

|

|

Ireland |

Planned |

Primary financing |

- | |

|

Spain |

Potential |

Primary financing |

- | |

|

France |

Financial Close |

Acquisition |

- | |

|

Norway |

Potential |

Primary financing |

- | |

|

UK |

Financial Close |

Primary financing |

476.6922 |

|

|

Norway |

Post-Procurement |

Primary Financing |

471.586 |

|

|

UK |

Announced |

Primary financing |

- | |

|

UK |

Approved |

Primary financing |

76.2698 |

|

|

Norway |

In Procurement |

Primary financing |

- |

Source: inspiratia | datalive

Most of the activity in 2020 was concentrated in the UK and Norway. This isn't surprising as the UK is the global leader of offshore wind, thus its expertise can easily be transferred to floating wind projects. The UK also saw the first commercial-scale floating wind farm – the 30MW Hywind project in Scotland – being commissioned in 2017 by Norwegian energy company Equinor.

Norway on the other hand is a major global oil and gas producer, and the country's expertise in offshore platform and shipping can be easily applied to floating wind projects. Norway is one of the few European countries that already have ports suitable for the commercial development and operation of FOW farms.

A notable UK deal is the financial close of the 50MW Kinkardine floating wind farm in Aberdeen, developed by the Spanish engineering firm Cobra Group. The developer managed to secure a £380 million (€420m US$472m) green loan financing for the project. French corporate and investment bank Natixis acted as sole green loan coordinator for the financing, as well as one of the mandated lead arrangers, underwriters and bookrunners.

Secondary market activity has also taken place in 2020. The energy major Total acquired a 20% stake in the 30MW EolMed floating wind project, in the south of France. The independent power producer Qair is the majority shareholder in the project, with other consortium members including the floating foundation-company Ideol, civil engineering company Bouygues Travaux Publics and the wind turbine manufacturer Senvion.

A new market: long-term potential

Floating wind turbines open up offshore wind opportunities to regions where the waters are too deep, and/or the seabed is unsuitable for bottom-fixed foundations to be economically viable. It has been estimated that 80% of the potential offshore wind resource in Europe (4,000GW) and Japan (500GW) and 60% of potential offshore wind resource in the USA (2,450GW) are in waters of 60 metres or deeper so floating wind turbines are crucial to tap into these resources.

According to IRENA, by 2030 around 5GW to 30GW of floating offshore wind capacity could be installed worldwide. Floating wind farms could cover 5% to 15% of the global offshore wind installed capacity — around 1TW — by 2050.

Tenders

As with bottom-fixed offshore wind farms, government support will play an important role for the advancement of FOW. Governments around the world have decided to introduce tenders for floating wind to support the technology's development.

2020 was the year that Japan kicked off its first public tender for FOW. The tender was launched in June [2020] for the construction and operation of the Goto floating wind farm, off the southern prefecture of Nagasaki. The wind farm will have a capacity of 16.8MW, with a feed-in-tariff of JPY36 (£0.26 €0.28 US$0.35) per KWh. The winner is due to be selected in June 2021.

The UK's decision to target 40GW of offshore wind energy and 1GW of floating wind by 2030 was a monumental decision taken this year [2020]. The round four CfD auction — set to take place in late 2021 — will allow floating offshore wind projects to bid for contracts for the first time. Floating wind will be included in pot two for less-established technologies.

As mentioned above, Norway has several exciting projects in the pipeline. The Utsira Nord and Sørlige Nordsjø Nord areas — located in the west of Haugesund and in the North Sea, respectively — will allow up to 4.5GW of new capacity to be built in the country and will spur developments in both floating and bottom-fixed installations. The applications for the two areas will launch on 1st January 2021.

Several companies have expressed their interest in the two areas, including energy giant Equinor, Danish renewable energy company Orsted and Norwegian offshore wind services firm Aker Offshore Wind.

The French government plans to organise three separate floating wind tenders in 2021 and 2022, each with a capacity of 250MW. The first, in 2021, will be in the southern waters off Brittany, while the other two in 2022 are planned for areas in the Mediterranean. The expected target strike prices are €120 (£110 US$146) per MWh and €110 (£101 US$134) per MWh, respectively.

Costs

Currently, floating wind turbines are significantly more expensive than bottom-fixed turbines. Clement Weber, co-founder of financial advisory Green Giraffe, had mentioned in a previous article that for a commercial FOW farm the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) is expected to be between US$121-146 (£90-108 €100-120 ) per MWh. The LCOE of bottom-fixed wind farms are between US$69-104 (£51-77 €56-85) per MWh according to the financial advisory Lazard.

The higher LCOE is due to the technological novelty and early industrialisation, but also due to higher cost of capital because of higher perceived technological risk. However, once the technology matures, we can expect floating wind to be cost-competitive with bottom-fixed technologies.

According to the trade body WindEurope, the LCOE of FOW could drop to US$97-121 (£72-90 €80-100 ) per MWh by 2025, and further fall to US$49-72 (£36-54 €40-60 ) per MWh by 2030.

Hydrogen production

An exciting announcement this past year was the selection of the Kincardine floating wind farm, off Aberdeen, Scotland for the Dolphyn wind-to-H2 project. The Dolphyn wind project is a pioneering plan to produce green hydrogen offshore.

The project plans to deploy a 2MW prototype system at the Kincardine site from 2024, producing hydrogen that will be pumped back to the city. The UK government-backed initiative, led by consultancy firm ERM, aims to desalinate seawater and use it to produce hydrogen via electrolysis, in a process powered by the offshore wind turbine that sits on each Dolphyn floating platform.

Hydrogen is one of the hottest topics right now. Using floating wind for hydrogen production opens up a new market for the technology, other than electricity generation, which may increase investor appetite.